What happened on September 19?

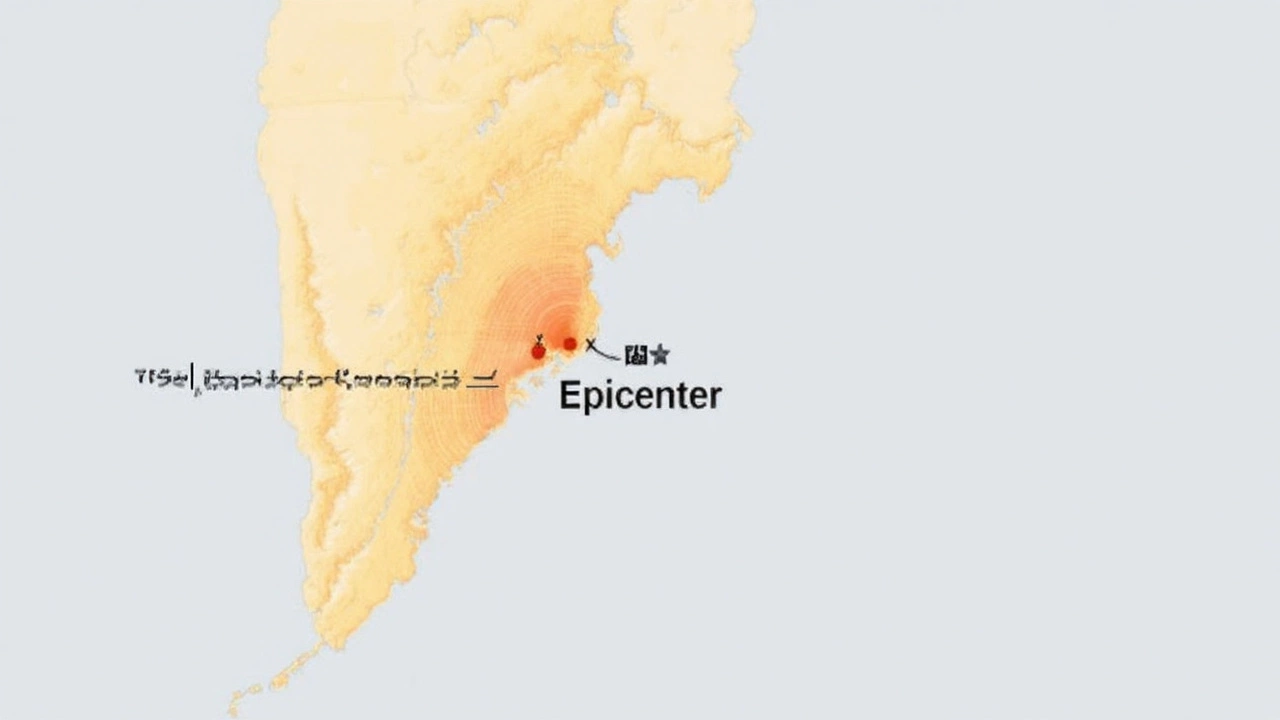

At 6:58 a.m. local time a 7.8‑magnitude earthquake ripped through the ocean floor off Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. The quake lasted roughly 40 seconds, releasing energy comparable to the blast of a small nuclear device. Seismographs recorded ground motion that spread over an area the size of Wyoming, rattling everything in its path.

In the two biggest cities on the peninsula—Petropavlovsk‑Kamchatsky and Yelizovo—residents felt shaking rated between MMI VI and MMI VI‑5, meaning strong to very strong. Concrete apartment blocks suffered broken wall sections and large cracks, yet quick inspections reported zero injuries or deaths. Local officials attribute the lack of casualties to the early hour, when most people were still at home and could evacuate interior rooms before any secondary hazards appeared.

Why the tsunami warning, and what did Alaska experience?

The epicenter sits in a classic subduction‑zone setting where the Pacific Plate dives beneath the Eurasian Plate. Such movements can displace huge volumes of water, prompting the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center to issue alerts across the basin within minutes. Alaska, over 4,000 km away, received a brief advisory that advised coastal residents to stay clear of beaches and monitor local sirens.

Fortunately, the wave heights that reached Alaskan shores stayed well under a foot, prompting officials to lift the advisory within an hour. The quick response illustrates how modern warning systems, refined after the 2011 Tōhoku disaster, can curb panic even when the source quake occurs far offshore.

This event is the second major tremor to hit essentially the same spot in less than a week; a similar 7.8 quake shook the region on September 13. Both shocks are part of a larger cascade that began with a colossal 8.8 megathrust quake on July 30, the strongest globally since the 2011 Japanese event. That July quake generated a Pacific‑wide tsunami with wave heights of about one meter in most places, though coastal communities in Kamchatka and Sakhalin reported higher run‑ups.

Seismologists expect a flurry of aftershocks in the coming weeks, some possibly reaching magnitude 5 or higher. The frequency should taper off, but the stress redistribution along the fault means that the area will remain seismically active for months, if not years. Researchers are closely monitoring micro‑seismic activity to refine hazard models for the Pacific Ring of Fire, where the Pacific Plate collides with the North American and Eurasian plates.

The twin September earthquakes underscore the fragility of infrastructure built on the volatile Kamchatka coast. While the Kamchatka earthquake caused visible damage, the lack of casualties highlights both the resilience of local building practices and the effectiveness of early warning protocols. Ongoing assessments will determine whether retrofitting programs need acceleration to better protect communities against future high‑magnitude events.