More than 56,000 people fled their homes in January 2025 as fighting exploded across Colombia’s northeast. Entire communities packed what they could and left, not because of a single battle, but because armed groups can attack in Colombia and step back into neighboring Venezuela to rest, rearm, and plan the next round. That sanctuary has turned a long, porous border into a conveyor belt of violence.

A border turned sanctuary

The flashpoint is Catatumbo, a rugged region in North Santander that sits right against Venezuela. It’s thick with coca fields, clandestine labs, and illegal mining sites. Whoever controls Catatumbo controls money, weapons, and routes. In mid-January 2025, the National Liberation Army (ELN) pushed to retake ground there, opening one of the fiercest campaigns Colombia has seen in years.

Human Rights Watch estimates more than 56,000 people were displaced in weeks. UNHCR says roughly 80,000 people were affected overall—harassed, trapped, or forced to move—nearly 47,000 of them children and adolescents. The humanitarian picture is brutal: families scattered; schools shut; clinics and aid convoys trying to reach towns where gunfire and landmines make travel risky.

The violence isn’t just firefights. It’s killings, kidnappings, forced disappearances, and forced child recruitment. In late January, Colombian authorities recovered the bodies of 13 FARC combatants, among them women and two boys pressed into war. The ELN alone held at least 22 hostages, including three children, who were released in March. The real number of captives is likely higher, because fear keeps many families silent.

Here’s what makes this cycle self-sustaining: ELN units and FARC dissidents move to Venezuelan territory when pressure rises. They find refuge in remote border communities and deep jungle. Colombian commanders say that in January raids they seized weapons tied to the Venezuelan Armed Forces—proof, in Bogotá’s view, of direct material support. Whether those guns were stolen, trafficked, or supplied is almost impossible to verify publicly, but the discovery bolstered long-standing accusations that irregular groups are more than just tolerated across the border.

To understand why the border matters so much, look at the economics. Drug money flows through Catatumbo’s corridors. So does gold and other minerals dug out by informal or illegal mines. These markets pay for guns, vehicles, phones, fuel, and the payrolls of fighters. When the state is weak—or absent—armed groups step in to tax everything that moves. If one side is pushed out, it adapts and resurfaces a few kilometers away, often on the other side of the river or ridge where Colombian patrols can’t follow.

Caracas has not publicly acknowledged sheltering Colombian guerrillas. In past disputes, Venezuelan officials have rejected such accusations and said they combat criminal groups inside their borders. What’s different now is the scale of the violence in Colombia and the volume of reporting from local officials, residents, and human rights groups documenting how fighters cross back and forth with ease.

Colombia has tried to respond with force. The government deployed more than 9,000 soldiers and roughly 800 police to hit ELN positions, protect roads, and secure towns across Catatumbo. Patrols are heavier, checkpoints tighter, and air assets more active. But firepower can only do so much when armed groups can retreat to another jurisdiction—especially one that’s politically hostile and hard to police even in the best of times.

All this is happening against a tense political backdrop. After Colombia’s 2016 peace deal with the main FARC insurgency, thousands laid down arms. But not all. FARC dissident fronts kept fighting, and the ELN stayed in the field. Bogotá opened talks with the ELN in 2022, hoping a ceasefire could calm hotspots like Catatumbo. Instead, the January offensive shattered confidence, and the government suspended talks in February 2025. On the ground, residents saw the result right away: more roadblocks, more threats, more gunmen marking doors and phones.

The human cost doesn’t stop at Colombia’s side of the line. Among the displaced are about 4,600 Venezuelan refugees and migrants who had fled their country’s collapse only to be uprooted again by a border war. It’s a tragic loop: people escape hunger, hyperinflation, and repression, settle in a Colombian hamlet, and then run again when the shooting starts. Aid groups now scramble to support both Colombian families and Venezuelan newcomers caught in the same crossfire.

When you map the border, the pattern is obvious. Villages tucked into mountains, river crossings that can’t be watched 24/7, dirt trails that skirt official posts, and jungle that can swallow a patrol in minutes. It’s terrain that frustrates even well-resourced armies. And on the Venezuelan side, where the state’s presence is thin and local powerbrokers hold sway, guerrillas and criminal bands carve out fiefdoms that look durable, not temporary.

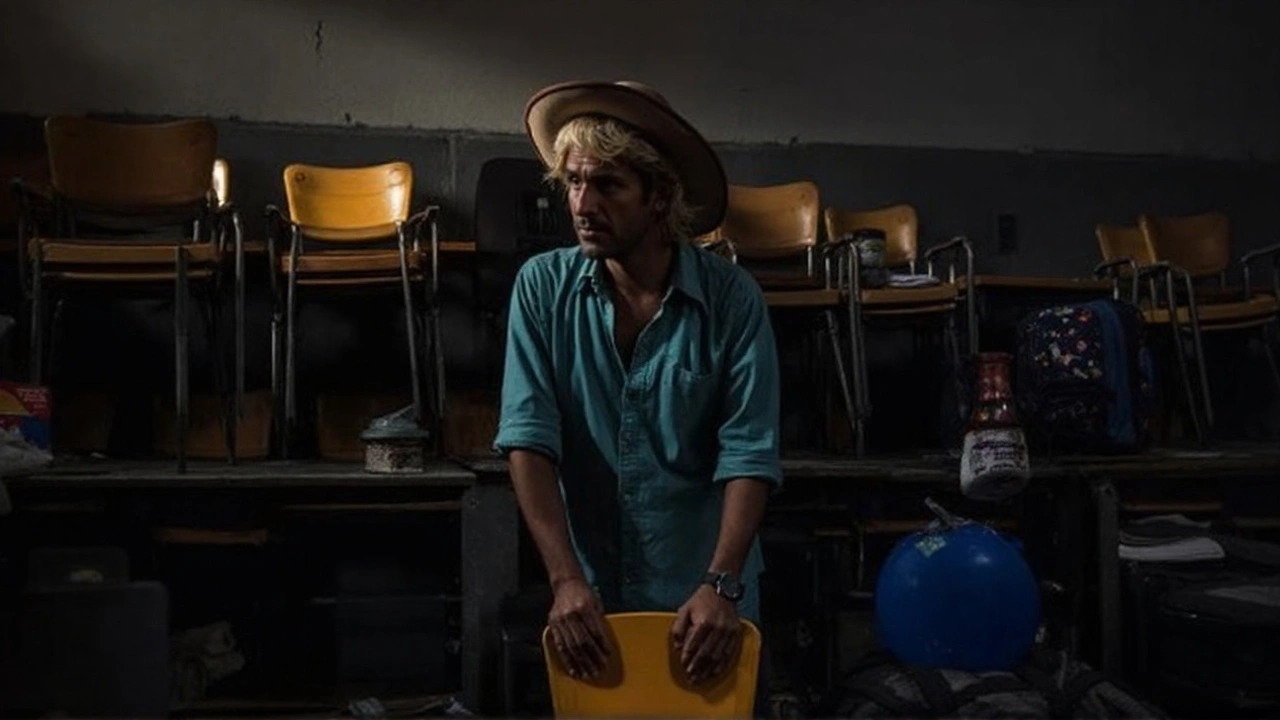

What does this look like for people living there day to day? It means rotating curfews ordered by armed men. It means families sending kids away to avoid recruitment. It means shopkeepers paying “fees” to whoever controls the road that week. It means farmers walking fields with a sixth sense for landmines, and health workers calculating which routes are safe enough to drive before dusk.

For the armed groups, Catatumbo is logistics heaven. They can coordinate on apps with disposable phones, stash fuel and ammo in the hills, and blend into migrant flows when needed. When Colombian forces surge, they fade across the line, switch uniforms, and wait. Then they sneak back to tax coca harvests, guard labs, and escort shipments north and west toward Caribbean and Pacific exits.

Colombia argues this isn’t just a bilateral problem. It’s regional. Cocaine made in Catatumbo doesn’t stay there. Gold mined illegally doesn’t either. The cash and commodities travel, and so do the networks that move them. That’s why European lawmakers and human rights organizations have weighed in, warning that the cocktail of armed groups, weak border control, and interstate friction could spill far beyond a single province or country.

On paper, there are ways to cool things down: joint patrols, intelligence sharing, hotlines between commanders, and neutral monitors. In practice, those tools need trust, and trust is in short supply. When a Colombian unit displays rifles stamped to a neighbor’s army, and that neighbor denies any role, cooperation stalls. Each day of stalemate is another day the war economy pays everyone except the families it uproots.

What this means for peace and the region

Peace talks work only if local people feel them in their daily lives. In Catatumbo, residents saw the opposite this year. The government paused negotiations with the ELN, and the armed group flexed its power on the ground. That whiplash makes it harder to restart talks later, because communities and soldiers alike ask the same question: will a paper deal change anything if fighters can run to a cross-border sanctuary whenever they choose?

The answer depends on whether that sanctuary closes. Even partial cooperation from Caracas—allowing observers, curbing known routes, or arresting specific commanders—would change the calculus. Without that, Colombia faces a grind: clear-and-hold operations that briefly stabilize towns, followed by the familiar return of roadblocks, extortion, and propaganda messages painted on walls overnight.

Meanwhile, the humanitarian needs keep growing. Displaced families need shelter, cash support, schooling for kids, and safer routes to return home or resettle. Clinics need supplies for trauma care and mental health support. Aid teams need secure access so they don’t become targets themselves. A predictable, well-funded response helps, but it won’t stem the flow if the fighting stays hot.

There’s also a generation at risk. Child recruitment isn’t just a statistic—it’s a strategy. Young teenagers learn to carry messages, cook for units, and then handle weapons. Pulling them back to school and keeping them there requires pressure on recruiters, reliable income for families, and community programs that make home feel safer than the camp. In areas where armed men set the rules, that’s a tall order.

The numbers tell the story of 2025 so far:

- Displacement in Catatumbo: more than 56,000 people in weeks, according to Human Rights Watch.

- Total affected: around 80,000 people, including roughly 47,000 children and adolescents, per UNHCR.

- Hostages: at least 22 held by the ELN, including three children, released in March; overall detentions likely higher.

- Bodies recovered: 13 FARC combatants found in late January, among them women and two child soldiers.

- Colombian deployment: over 9,000 soldiers and nearly 800 police in simultaneous operations.

- Secondary displacement: about 4,600 Venezuelan refugees and migrants uprooted again inside Colombia.

These aren’t isolated facts. They add up to a cross-border system that keeps paying off for the people with guns and keeps punishing the people without them. When territory in Colombia becomes too hot, the safe option is to step into Venezuela, reorganize, and wait for the moment to strike again. That rhythm explains why large military operations don’t always reduce overall harm for civilians—and why, in the absence of joint action, the cycle persists.

Diplomatically, the space is narrowing. International actors are speaking out about Colombia’s worsening security, and many are blunt about the cross-border dimension. But statements don’t shut down labs or free hostages. Real progress requires practical steps: border checkpoints that stay staffed, prosecutions that stick, and a shared commitment to shield civilians even as politics stays tense.

There’s one more layer that’s easy to miss: the economy of fear. When extortion, road taxes, and contraband become normal, people adjust to survive. They keep quiet. They pay. They look away. It takes time—and tangible safety—to reverse that. Parents need to see kids return from school unharmed. Traders need to drive without bribes. Farmers need to harvest without a gunman deciding what their crop is worth.

For now, Catatumbo sits in limbo. The border is open enough for fighters and contraband, but not open enough for real cooperation. The Venezuelan state’s role remains disputed, but the signatures of its territory—safe havens, weapons, and back routes—are written all over the conflict. Unless that changes, Colombia’s peace agenda will keep colliding with a hard reality at the edge of the map.